Welly

May 2025

We meet Welly in the smallest and most iconic venue in Bristol, The Louisiana. It’s presented household names like Amy Winehouse and The White Stripes, but today they’re taking a more domestic swing; Welly are debuting their first album, Big in the Suburbs. It lives up to the name in buckets and spades.

The band have developed a reputation for British slice-of-life songs, but it’s their gigs that make the fans. In pinafores and PE kits, they swing from twee comedy bits to moments of real popstar potential. It’s such a fun show: the kind of shameless you can be before you realise what’s expected of you, your country’s stiff upper lip. They seem comfortable throwing themselves in as the novelty contender in an otherwise fairly serious group of bands in their early twenties.

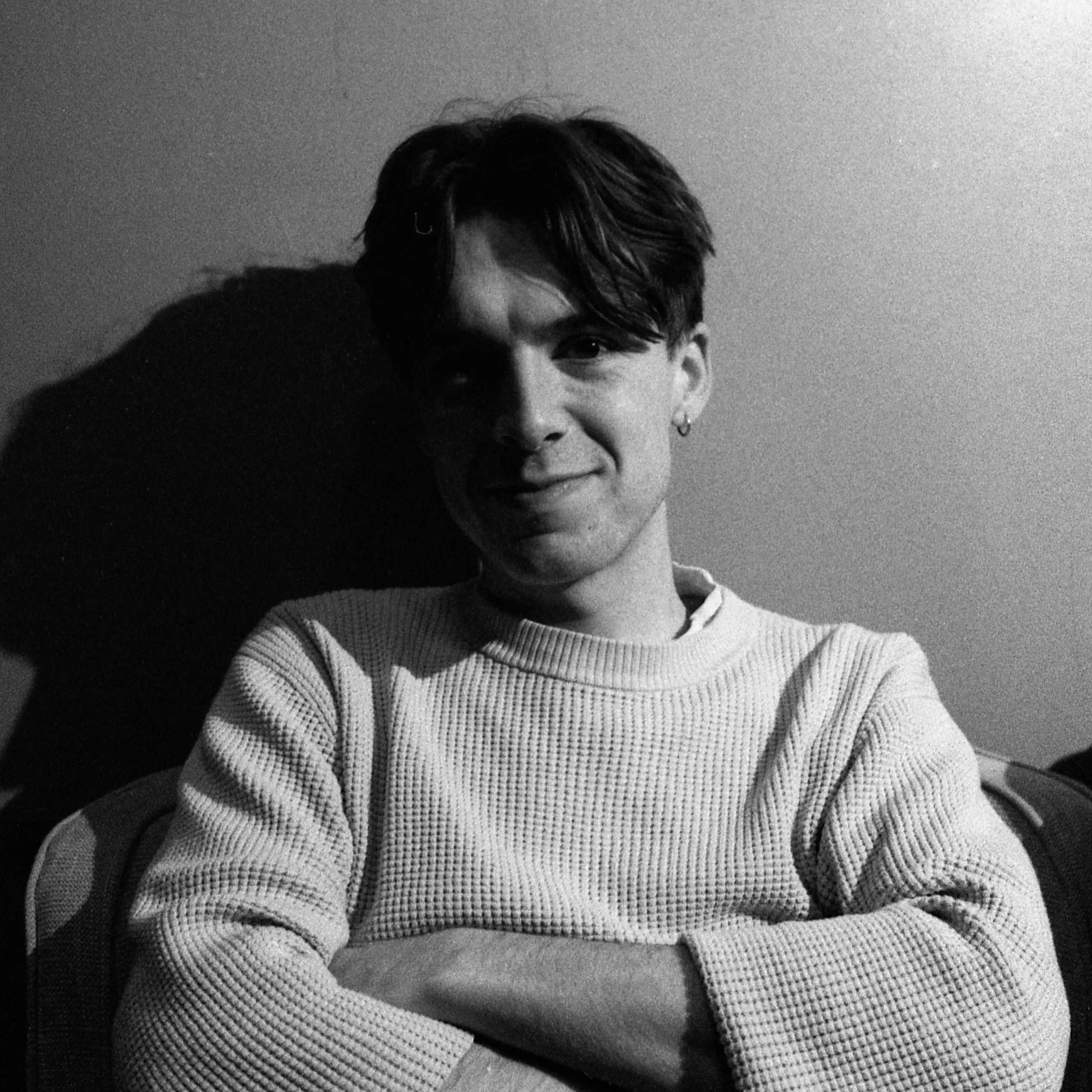

But when Welly – Elliot Hall - emerges, there’s a quick-draw understanding. Fronted by a different boy, the band could have veered into something square or overwrought, but it’s through his presence that their prancing about is undercut by the conventional traditionalism of a rakish frontman. Think Damon Albarn, Ian Brown, Brett Anderson; he’s even got the earring. He sticks his hand out to shake with a school prefect’s eagerness: the voice of a racehorse commentator, the confidence of a weeknight comedian, the cheekbones of a glam rock star. It’s his band, but he’s keen to let you know it’s a family affair. Jacob (bass), Hanna (synths), Matt (guitar), and Joe (the same) - queue up like they’re waiting on a coach for a school trip.

‘ I would sell my skin to join the Zeitgeist.’

I ask how the band came about, and Elliot chips in. ‘I moved to Brighton from Southampton, and convinced Joe and Jacob to join me. I met Matt the first day of university - and promptly met no one else because he fulfilled all the criteria – and Hannah worked behind the bar at the Indie Night at Green Door. I got drunk and asked her to join the band, and she thought I was coming on to her.’ He laughs, and you sort of have to wonder whether he was. A pause. ‘Rung one of the ladder is a lot of fun.’

Did things change for them when they moved to Brighton?

‘Moving helped a lot, because I was homesick for the first time: hence why the album’s all about suburbia, because all these things I hated and tried to escape from came back in a different light.’ The songs had been kicking around for five or six years, written before and during university. Joe says he’s come out of his shell since moving to Brighton - ‘I lived in Swansea before, so to me it’s like I’ve moved to Las Vegas.’

Their bread and butter is found in their immediate vicinity – day trips from Dover, gap yah girls, gigs at the scout hall – and it’s in this way that they’ve made the album’s core concept so airtight, so well conceptualised. You almost have to wonder where they’ll go from here. ‘You only get one attempt to make your first album, and we got to make it the way we wanted,’ Elliot says. ‘I can’t believe our management and the label let me get away with saying, “No, we’re gonna make it all ourselves.” Fuck knows where the money went. But these songs are all homemade.’ He laughs. ‘I’m aware you haven’t asked me a question in quite a long time.’

I’ve always liked music that sets its own timer, writes its own expiry date; Chas & Dave talking about plays on the wireless and Just William books, Beastie Boys pining after a girl on pre-Guiliani 8th Ave. & 42nd St. I think it shows faith in a story to know it will still be good when no one gets the reference. It’s like that with Welly. Half of what they say runs the risk of being dated in 20 years, from Brexit - It goes from ring-a-ring-ring-road / To a fear of using Euros – to the death of the high street - I want it cashless, I want it trendy / But I also want a Costa and a massive Aldi - but it’s endearing that they don’t seem to mind. It also means, inevitably, that there’s something quite zeitgeisty about the whole ordeal. I tell them that, and Elliot laughs. ‘I would sell my skin to join the zeitgeist.

‘The only way you can, I think, is with authenticity, and to write about what you see out the window. I tried to write love songs and they were crap, because I haven’t been in love much. But I could speak about what I thought of England, because a lot of people growing up our age - I include you in this,’ he gestures to me, ‘got the same TV, the same cultural and social influences. The music you can’t cheat; people will just like it or not. If I write something I enjoy, and I’ve got something out of, then if other people like it that’s fantastic.’

I tell Elliot he’s following in quite an English tradition of observational humour.

‘Yeah, whether there’s a market for it or not these days, I don’t know.’ A wry smile. ‘I like W.H. Auden, William Beckford, Carol Ann Duffy, Philip Larkin. There’s that awful Matty Healy quote: from the left hand of Miles Davis or the right tweeter of Aphex Twin. A lot of Welly stuff is inspired by modern electronica and '90s house; the way we use a drum machine, say; it’s all four on the floor beats. I’m trying to mix it with that, but I’ve never got that deep into it, because no one really gives a toss: if ABBA can do it with the same 12 notes, why can’t we?’

Does he get most of his inspiration from past cycles of British music?

‘A little bit from the current era. I can listen to a Sabrina Carpenter or Chappell Roan record and appreciate it, but it’s not really made for someone like me. I find '60s beat combos inspiring, or being the band where the shtick is that when we play, we’re really chipper. Or '80s DIY indie: putting on free raves. I’d love to do that now.’

They were recording Big in the Suburbs a year ago, so they’ve had some time to reflect on the process. Elliot spent some time alone putting together drum tracks and sketched song drafts, but the recording was over just two weeks at his dad’s house in Scotland. ‘The routine was that I’d wake up from some horrific dream; the Pet Shop Boys dying, maybe. We’d wake up, me and Matt would go through a take. In the evenings we’d get drunk on this five-pound sparkling wine from Tesco’s called Barigny. Maybe some Scrabble.’

Jacob leans in to correct him. ‘We played Scrabble once, and it got so violent we vowed to never play again.’ I tell them they strike me as people who’d be good at it. With choruses like Civics, Eurythmics, Economics, Marx, and lines like Commemorating relatives in tessellating terraces, you’d be hard pressed not to stumble onto a few triple-word scores. Elliot changes course. ‘This house is about 20 miles outside of Glasgow, the nearest shop is an hour away. Harvey [Payne], who makes our music videos, came to make the video for ‘Shopping’ in Dundee on the last day. He came to the house, and he went, ‘not only is there a vibe, but there is a smell.’

For the tour, Joe says they’ve been to towns where bands don’t usually go. ‘Weston-super-Mare, Carlisle, Hartlepool, Worthing.’ They’ve seen most of the UK from the inside of scout halls. They ask Hanna, who grew up elsewhere, what she’d expected the country to look like. ‘It’s a lot of motorway. You can find a lovely thing in every city.’ Elliot says the place they were staying in Middlesbrough was between a Wetherspoons and a Botox clinic called Skinfinity. It seems like they love being on the road. Elliot smiles. ‘You can only do it because you think it’s a laugh. I don’t understand bands who are genuinely miserable; you have to realise how frivolous it all is.’

Full article and more images in NEGATIVLAND - ISSUE TWO

Words: Kate Jeffrie

Photos: Kirkland Childs & Isaac Stubbings

Illustrations: Iris Ejlskov